Editor’s note: Want to contribute a guest blog post? Contact us.

Editor’s note: Want to contribute a guest blog post? Contact us.

By Samuel Scott

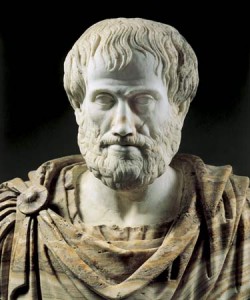

When I was a freshman journalism-major at Boston University in the spring of 1999, one of the required liberal-arts courses was “Introduction to Ethics” since reporters, of course, should strive to be ethical. One of the texts that I have always remembered was Aristotle’s “Nicomachean Ethics,” and Book Three details with the philosopher’s view of “voluntary” and “involuntary” actions and the ethics associated with each. (My professor back then had opened his discussion with, I believe, this rhetorical question: “Am if I kill a man while drunk, was my action ‘voluntary,’ and am I ethically responsible?”)

Recently, I started watching the second and third seasons of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” again, and I started thinking about these issues while seeing Buffy “kill” Ted and Faith kill the deputy mayor of Sunnydale. In Nicomachean ethical terms, I wondered, were their actions voluntary, and are the two slayers ethically culpable in either or both of the circumstances?

Buffy’s Voluntary and Involuntary Actions

First, of course, we need to define our terms. For the sake of brevity, I will state Aristotle’s discussion of the ethics of “voluntary” and “involuntary” using the following summary from the study notes of Gradesaver (the following are direct statements from the guide, with my few clarifications in brackets):

Involuntary action:

- An involuntary action is something done by [outside] force or through [one’s] ignorance

- For an action to be involuntary, there must be some external principle causing the action and the person must not contribute anything to the action

Voluntary action:

- A voluntary action is one in which the agent of the action knows the particulars on which the action depends

- An action performed through temper or desire is still voluntary

- Actions concerning the means to an end are in accordance with intention are voluntary

- [Individual] actions [that] we are in charge of what we are doing at every step of the way [are voluntary]

- Habits are still voluntary because one can choose whether to act or not to act in a certain manner from the outset

Aristotle’s examples of involuntary actions include revealing a secret by accident, misfiring a catapult, or mistakenly giving a person medicine that kills him (actions out of ignorance) or an action in the context of that “the moving principle is outside, being a principle in which nothing is contributed by the person who acts — or rather, is acted upon.” A voluntary action is when “the moving principle is in the agent himself, he being aware of the particular circumstances of the action.” In other words, it is when a person takes direct action and is aware of the causes and effects of the action.

(Of course, there are possible gray areas. An action taking out of anger, desire, or drunkenness — as in my professor’s example — is still, according to Aristotle, “voluntary” because one makes the conscious choice to become drunk or act on his emotions. However, these types of actions are somewhat less “voluntary” than, say, a cold, thought-out plan to purchase a gun and rob a bank.)

In the so-called Buffyverse, there are several examples of involuntary actions:

- The most-common example, of course, is a human victim who is turned into a vampire. A girl who makes out with someone who is seemingly human is ignorant of his true nature and what will shortly occur. Moreover, she is primarily being acted upon by an external force rather than directly taking an action herself. In short, she made an ignorant, unintentional mistake. (This could be used in parallel to a discussion on what level of ethical responsibility, if any, a woman has who is partially intimate with a man and is then date-raped.)

- When Faith attacked the deputy mayor, a human, and staked him through the heart, she was ignorant that he was human. As the episode reveals, Buffy and Faith were tracking a vampire, and the person suddenly approached them out of nowhere.

And there are many types of voluntary actions (particularly in the two seasons that I am currently watching again):

- The mayor of Sunnydale chooses in Season 3 to have demon patrons to ensure a long life (and then an Ascension at the end of Season 3) while being fully aware of the consequences

- Xander, in the finale of Season 2, chooses not to tell Buffy, who is on her way to kill the (evil) Angel, that Willow is trying to perform a spell that will restore Angel’s soul — he, we can infer from his comments in prior episodes, wants Buffy to kill him even though there is a chance that Willow’s spell may work

- Vampires who attack humans are performing voluntary actions in Aristotle’s eyes because being wicked itself is a voluntary choice (on the part of the demon) rather than just “vampires being vampires” — after all, “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” shows various demons and vampires choosing not to attack humans and living virtuous lives

The Ethics of Buffy’s Actions

A further summary from Gradesaver:

- Only voluntary actions can be considered virtuous [or not]

- It is unreasonable to think that only good is voluntary while evil is involuntary, for that would contradict our previous conclusion that human beings are the cause of their own actions

A person, according to Aristotle, can only be praised or condemned for a voluntary action on his or her part since people are not responsible — or should not be held responsible — for involuntary actions. In this ethical paradigm, people like Faith are not to be blamed for the death of the deputy mayor and people are not to be held responsible for being turned into vampires (excepting the rare cases we see, like with Buffy’s old high-school friend from Los Angeles in Season 2 (“Lie to Me”), when people actively seek that “change”).

However, we can judge the actions of people in other circumstances that are voluntary. Xander, as most seem to agree, was ethically wrong not to tell Buffy about Willow’s spell, but Buffy’s “killing” of Ted is a situation that is more interesting in an ethical context.

First, a summary of the context. Buffy’s mother is dating Ted, a man whom Buffy dislikes. She even spies on him at work. One night, after disrespecting Ted at dinner, Buffy returns home through the window and sees Ted sitting in her bedroom, reading her diary. He says that she will do whatever he says, or he will show the diary to Buffy’s mother. When Ted starts to leave, Buffy tries to stop him and demands that he return the diary. “Take your hand off me,” he says. “No,” Buffy replies. Ted hits her in the face, hard. “I was so hoping you’d do that,” she responds. Buffy hits Ted, the two begin fighting, and Buffy quickly gains the advantage. She side-kicks Ted multiple times with enough force to push him out through the hallway, and then he falls down the stairs and breaks his neck.

See the episode:

Of course, people who have seen “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” know that Ted was a robot — but neither the characters nor the audience at the time knew this fact until after Buffy’s attack. In the situational context, Buffy believed that she was attacking — and then had killed (directly or not) — a human being. (In legal terms, I believe the case would be a matter of manslaughter and not murder.) So, in a Nicomachean context, was Buffy’s voluntary action ethical?

In simple terms, Aristotle defines “ethical” as the Golden Mean — a point between two unethical ends of a relevant spectrum. The common example cited is that the ethical attribute of “bravery” is the middle ground between “cowardice” and “stupidity.” Cowardice is never fighting at all, even in defense of one’s city (like Sunnydale). Stupidity is rushing into battle against impossible odds while knowing that one will be killed (and all for nothing, as a result).

In the Buffyverse context of the Slayer, the two extremes would be Buffy either never using her superhero strength at all against anyone (for whatever reason) and using her powers against anything and everything (human and demon). (See a prior essay on the nature of authority in “Buffy the Vampire Slayer.”) The Golden Mean, to Aristotle, would still lie somewhere in the middle. In the context of Ted, Buffy moved to far to the latter end of the spectrum when she used her supernatural gifts to harm a human. As a result, Aristotle would say that her voluntary action was unethical.

After all, as Buffy herself says later in the episode: “I had a fight, and I lost my temper… he was a person, and I killed him… I’m the Slayer. I had no right to hit him like that.”

Samuel Scott is the founder and publisher of Buffy the Vampire Slayer Online. You can follow him on Facebook, LinkedIn, Google+, and Twitter as well as on his personal website.

Like this post? Submit it to Whedonesque!